On Jan. 9, Tonja Stelly had to be in two places at once. That’s nothing new to her. It’s become a tradition over the past three years, whenever the NBA and NHL schedules collide in just the right way.

The Knicks were playing the Portland Trail Blazers inside the world’s most famous arena, Madison Square Garden, that Tuesday. Her son Quentin Grimes, a guard with the Knicks at the time and currently with the Detroit Pistons, had a 7:30 p.m. tipoff. Twenty miles to the east, her son Tyler Myers, a defenseman for the Vancouver Canucks, had a game at the same time, against the New York Islanders in Elmont, N.Y.

So Tonja and her husband, Ken, along with her brother and his family, hopped on a flight from Texas to New York. Tonja and Ken went to UBS Arena to watch Tyler, spending two hours bending their necks between the action in front of them and the cell phone on her lap, which featured the Knicks game. Her brother and his family were doing the same thing at MSG, with the sounds of a basketball kissing the hardwood and the Canucks-Islanders game on a tiny screen nestled in front of them.

“The people sitting around us, of course, were like, ‘Wow! You’re really into sports,’” Tonja said. “We were like, ‘Yes, yes we are.’”

Everyone knows about Donna Kelce, the mother of NFL players Travis and Jason Kelce. Most people are familiar with Sonya Curry, the mother of NBA players Stephen and Seth Curry. Very few, though, are familiar with Tonja Stelly, the mother of the only NBA-NHL brother tandem in history.

She’s a sports mom and former athlete herself, having played basketball at Fort Hays State University back in her home state of Kansas. Quentin and Tyler are her only children, and from October to April, she travels around the country, bouncing between packed basketball arenas and frigid hockey arenas to see them compete.

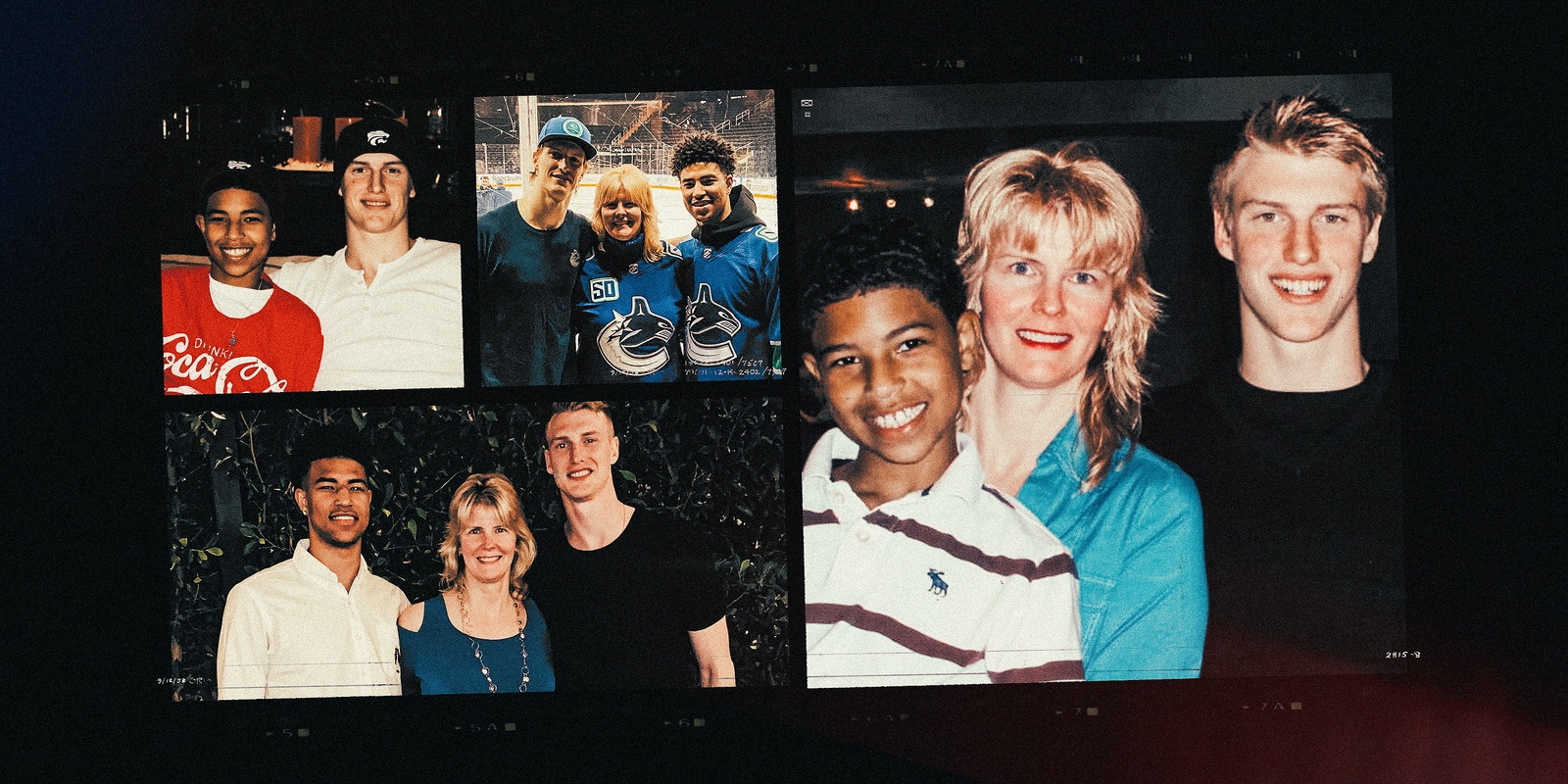

She gave birth to both in Houston 10 years apart — Tyler on Feb. 1, 1990, and Quentin on May 8, 2000 — but they have different fathers. As a result, they grew up apart in separate households, seeing one another only a few times a year, if that.

“I was like a single child,” Quentin said, recalling his upbringing.

Three months after Quentin was born, Tyler moved to Calgary with his father, Paul, who was in the oil and gas business, and that’s where the hockey took hold. He had already started playing the sport in Texas — around age 7 — but the sport’s ubiquity in Canada helped him dive deeper into the game, which set him on a path to the NHL.

In the summers, and sometimes during spring break, Tyler would travel back to Texas to spend time with his mom and his little brother. Tonja would take them out to play tennis or basketball, swim or take ride bikes. They’d take annual 22-hour round-trip car rides to go see Tonja’s side of the family in Kansas. She did everything she could to make sure her sons had a relationship, even though they lived, essentially, a country away from one another.

(Photos courtesy of Tonja Stelly)

“It was very difficult when you’ve only got six to eight weeks during the summer to put that together,” she said. “But we would do things as a family unit and individually.”

Things like letting them play video games together and take turns on choosing where to eat dinner.

“They would pick different things being that Quentin was 4 and 5 and then Tyler was 14 and 15,” she said.

As Tyler entered his teenage years, the demands of junior hockey kept him away longer. But Tonja and Quentin would venture to Kelowna, B.C., to watch him play in junior and did the same when he broke into the NHL. Quentin was 8 when the Buffalo Sabres selected Tyler 12th in the 2008 NHL Draft. At 6 feet 8 inches, he became one of the tallest players in NHL history and quickly made an impact for the Sabres, who made the playoffs his rookie season. Shortly after Quentin turned 10, Tyler won the Calder Trophy for the league’s best rookie. He finished in the top 20 for the Norris Trophy, which honors the league’s best all-around defenseman, in each of his first two seasons.

The Sabres playoff series spurred Quentin’s appreciation for the sport for more than his association to it via Tyler.

“I remember seeing that atmosphere, and I think I took more interest than the regular Texan watching hockey,” he said. “I tell people all the time, with playoff hockey, I don’t think there’s a better atmosphere — banging on the glass, shoving, pushing, hip-checking, it’s super fast-paced, people throw stuff on the ice. They’re not doing that at a basketball game.” (Well, unless they’re Jamal Murray, but we digress.)

Around 9, Quentin began playing AAU basketball, and like his older brother, quickly stood out among his peers. By high school, it was apparent he’d follow in the footsteps of his basketball-playing parents. Tonja Nuss was a 5-10 guard on the 1985-86 Fort Hays team that went 18-12. His father, Marshall Grimes, was a 6-foot guard for Santa Clara and Louisiana-Lafayette in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

As a five-star recruit, Quentin initially played at Kansas before transferring to Houston after his freshman season. There, he blossomed into the leading scorer on the Cougars’ 2021 Final Four team, leading to him being selected 25th by the Knicks in the NBA Draft.

Only so many people know what it takes to be a professional athlete. And luckily for Quentin, his brother is one of them. Tyler could share how to train like a professional athlete, and how to eat like one. But he also wanted to let Quentin “carve his own path.”

“As an athlete, I know I don’t want to bombard him with too much advice or too much that might overwhelm him, but certainly little things here and there I’ll throw at him,” Tyler said. “Even last month, I was reading this book and I forwarded him what it was all about and told him to check it out. Just little things like that here and there, that I think can help him out, and anything that I’ve gone through along the way.”

The NBA and NHL schedules don’t overlap in an easy way for Tyler and Quentin to see each other play live. “We kind of have to keep tabs on each other from afar,” Tyler said.

But Quentin playing in New York to begin his career helped when the Canucks would swing through the city to play the Rangers, Islanders and Devils in succession. Tyler attended one of Quentin’s home games a couple of years ago, and they shared a couple of dinners together.

“As you see them mature into adults and find their way, especially since Tyler was gone at such a young age, to see that circle back to them now as adults is pretty special,” Tonja said while fighting back tears. “Pretty special.”

(Photos courtesy of Tonja Stelly)

When Tyler spoke by phone earlier this week, he was already excited for his mom and brother to come to Vancouver this week for the Canucks’ second-round playoff series against the Edmonton Oilers.

Equally as exciting in the days leading up to Mother’s Day, Quentin will get to meet Tyler’s three children (Tristan, Skylar and Tatum) for the first time.

“It’ll be awesome,” Tyler said in advance of the visit. “The kids will get to meet their uncle, and it’ll be great for them to connect.”

For Tonja, who helped raise two boys with different cultural backgrounds, interests and upbringings, “It’s a pretty special weekend.”

What could be more special?

Well, Quentin has one year left on his contract with the Pistons at $4.2 million and could potentially re-sign long term. Tyler is pulling in $6 million this season and is set to become a free agent July 1.

A lot would have to line up, but it’s awfully tempting to wonder if Tonja’s sons could one day call the same arena and the same city home. After all, the Detroit Red Wings could potentially be in the market for a right-handed defenseman this summer.

“I think they (could use one), too,” Tonja said with a laugh. “That would be so awesome.”

(Photo illustration: Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; photos courtesy of Tonja Stelly )