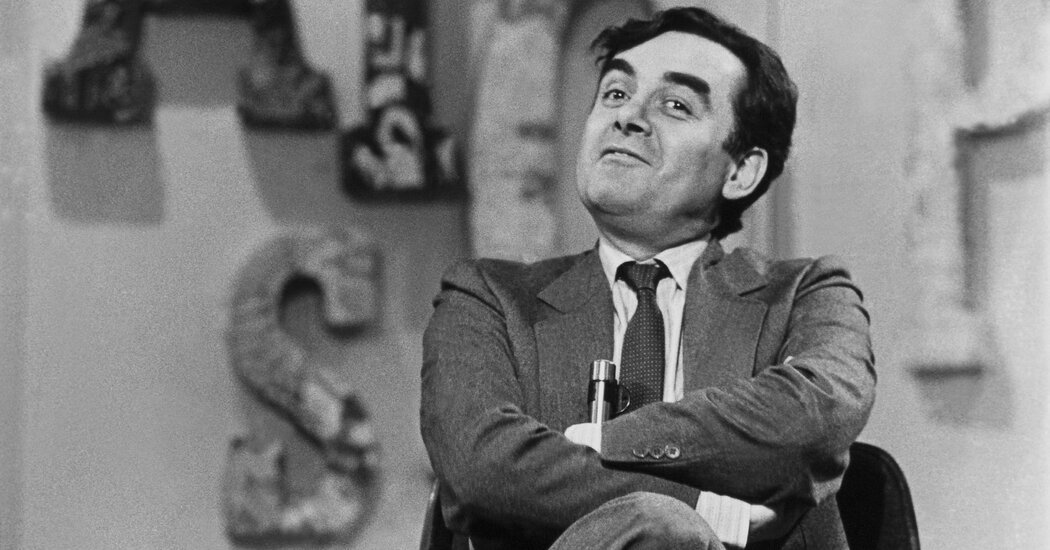

Bernard Pivot, a French television host who made and unmade writers with a weekly book chat program that drew millions of viewers, died on Monday in Neuilly-sur-Seine, outside Paris. He was 89.

His death, in a hospital after being diagnosed with cancer, was confirmed by his daughter Cécile Pivot.

From 1975 to 1990, France watched Mr. Pivot on Friday evenings to decide what to read next. The country watched him cajole, needle and flatter novelists, memoirists, politicians and actors, and the next day went out to bookstores for tables marked “Apostrophes,” the name of Mr. Pivot’s show.

In a French universe where serious writers and intellectuals jostle ferociously for the public’s attention to become superstars, Mr. Pivot never competed with his guests. He achieved a kind of elevated chitchat that flattered his audience without taxing his invitees.

During the program’s heyday in the 1980s, French publishers estimated that “Apostrophes” drove a third of the country’s book sales. So great was Mr. Pivot’s influence that, in 1982, one of President François Mitterrand’s advisers, the leftist intellectual Régis Debray, vowed to get “rid” of the power of “a single person who has real dictatorial power over the book market.”

But the president stepped in to stanch the resulting outcry, reaffirming Mr. Pivot’s power.

Mr. Mitterrand announced that he enjoyed Mr. Pivot’s program; he had himself appeared on “Apostrophes” in its early days to push his new book of memoirs. Mr. Pivot met Mr. Mitterrand’s condescension with good humor. The young television presenter’s trademarks were already evident in that 1975 episode: earnest, keen, attentive, affable, respectful and leaning forward to gently provoke.

He was conscious of his power without appearing to revel in it. “The slightest doubt on my part can put an end to the life of a book,” he told Le Monde in 2016.

President Emmanuel Macron of France, reacting to the death on social media, wrote that Mr. Pivot had been “a transmitter, popular and demanding, dear to the heart of the French.”

Mr. Pivot’s death made up the front page of the popular tabloid newspaper Le Parisien on Tuesday, with the headline, “The Man Who Made Us Love Books.”

Still, “Apostrophes” had its low moments, which Mr. Pivot came to regret in later years: In March 1990, he welcomed the writer Gabriel Matzneff who, grinning, boasted of the kind of exploits that 20 years later put him under ongoing criminal investigations for the rape of minors. “He’s a real sexual education teacher,” Mr. Pivot had said with good humor while introducing Mr. Matzneff. “He collects little sweeties.”

The other guests chuckled, with one exception: the Canadian writer Denise Bombardier.

Visibly disgusted, she called Mr. Matzneff “pitiful,” and said that in Canada, “we defend the right to dignity, and the rights of children,” adding that “these little girls of 14 or 15 were not only seduced, they were subjected to what is called, in the relations between adults and minors, an abuse of power.” She said Mr. Matzneff’s victims had been “sullied,” probably “for the rest of their lives.” As the discussion continued — Mr. Matzneff professed to be indignant at her intervention — Ms. Bombardier added: “No civilized country is like this.”

At the end of 2019, with the accusations against Mr. Matzneff accumulating, the old video drew outrage. Mr. Pivot responded: “As the host of a literary television show, I would have needed a great deal of lucidity and force of character to not be part of a liberty which my colleagues in the written press and in radio accommodated themselves to.”

On his show, there were sometimes confrontations between rivals; often it was just Mr. Pivot and a guest. Six million people watched him, and nearly everybody wanted to be on his show.

And nearly everybody was, including French literary giants like Marguerite Duras, Patrick Modiano, Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio, Marguerite Yourcenar and Georges Simenon. On one episode, Vladimir Nabokov, featured to talk about his novel “Lolita,” demanded that a teapot filled with whiskey be placed at his disposal and that the questions be submitted in advance; he simply read the answers. On another, a haggard-looking Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, not long out of the Soviet Union, spoke through an interpreter.

Mr. Pivot told the historian Pierre Nora in 1990 in the magazine Le Débat after the show had ended that his favorite programs had been with the greats whose residences he had been permitted to enter — citing the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, among others. “I left them with the spirit of a conqueror who had slipped into the private life of a ‘great man,’” he told Mr. Nora. “I left also with the delicious feeling of being a thief and a predator.”

Most of Mr. Pivot’s guests have since been forgotten, as he acknowledged in the interview with Mr. Nora. “In 15 and a half years, how many forgotten titles, covered over by other forgotten titles! But journalism, as I conceive it, isn’t necessarily only about what is beautiful, profound and lasting,” he said. Mr. Solzhenitsyn, he conceded, “made me feel really, really tiny.”

The responses he elicited were often perfectly ordinary, humanizing his exalted guests. “Literature is just a funny thing,” Ms. Duras said quietly, after winning the prestigious Goncourt Prize in 1984.

The television host wasn’t satisfied with her remark. “But, but, how is it that you create this style?” he pressed. “Oh, I just say things as they come to me,” Ms. Duras answered. “I’m in a hurry to catch things.”

A host of American writers appeared on the program, too: William Styron, Susan Sontag, Henry Kissinger, Norman Mailer, Mary McCarthy and others. The poet Charles Bukowski was on in 1978, drunken and downing bottles of Sancerre, molesting a fellow guest and getting kicked off the platform. “Bukowski, go to hell, you’re bugging us!” the French writer François Cavanna, a fellow guest, yelled. On a later program, a youthful Paul Auster basked in his host’s praise of the American writer’s French.

Bernard Claude Pivot was born on May 5, 1935, in Lyon, to Charles and Marie-Louise (Dumas) Pivot, who had a grocery store in the city. He attended schools in Quincié-en-Beaujolais and Lyon, enrolled at the University of Lyon as a law student and graduated from the Centre de Formation des Journalistes in Paris in 1957.

In 1958, he was hired by Figaro Littéraire, the literary supplement to the newspaper Le Figaro, to write the sort of tidbits about the literary world that the French press delighted in, and Mr. Pivot was launched. He had various television and radio programs in the early 1970s, helped launch Lire, a magazine about books, and on Jan. 10, 1975, at 9:30 p.m., aired his first of 723 episodes of “Apostrophes.” Another program Mr. Pivot hosted, “Bouillon de Culture,” had a 10-year run, ending in 2001. In 2014, he became president of the Goncourt Academy, which awards one of France’s most prestigious literary prizes, a position he kept until 2019.

In 1992, Mr. Pivot refused the Legion d’Honneur, France’s highest civilian honor, from the French government, saying that working journalists should not accept such an award.

“My father was very modest,” his daughter Cécile, also a journalist, said in an interview. “He didn’t want to have anything to do with that.”

Mr. Pivot was also the author of nearly two dozen works, principally about reading, and several dictionaries.

In addition to his daughter Cécile, Mr. Pivot is survived by another daughter, Agnès Pivot, a brother, Jean-Charles, a sister, Anne-Marie Mathey, and three grandchildren.

“Do I have an interview technique?” he asked Mr. Nora, rhetorically, in the 1990 interview. “No. I have a way of being, of listening, of speaking, of asking again, that comes naturally to me, that existed before I started doing TV, and that will exist when I no longer do it.”

Aurelien Breeden contributed reporting from Paris.