The president was livid. He had just been shown pictures of civilians killed by Israeli shelling, including a small baby with an arm blown off. He ordered aides to get the Israeli prime minister on the phone and then dressed him down sharply.

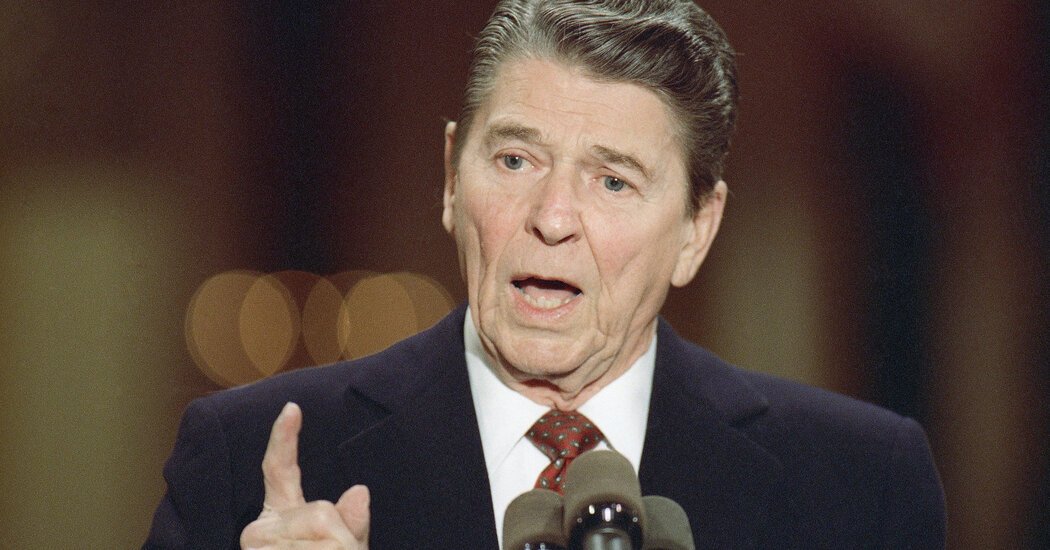

The president was Ronald Reagan, the year was 1982, and the battlefield was Lebanon, where Israelis were attacking Palestinian fighters. The conversation Mr. Reagan had with Prime Minister Menachem Begin that day, Aug. 12, would be one of the few times aides ever heard the usually mild-mannered president so exercised.

“It is a holocaust,” Mr. Reagan told Mr. Begin angrily.

Mr. Begin, whose parents and brother were killed by the Nazis, snapped back, “Mr. President, I know all about a holocaust.”

Nonetheless, Mr. Reagan retorted, it had to stop. Mr. Begin heeded the demand. Twenty minutes later, he called back and told the president that he had ordered a halt to the shelling. “I didn’t know I had that kind of power,” Mr. Reagan marveled to aides afterward.

It would not be the only time he would use it to rein in Israel. In fact, Mr. Reagan used the power of American arms several times to influence Israeli war policy, at different points ordering warplanes and cluster munitions to be delayed or withheld. His actions take on new meaning four decades later, as President Biden delays a shipment of bombs and threatens to withhold other offensive weapons from Israel if it attacks Rafah, in southern Gaza.

Even as Republicans rail against Mr. Biden, accusing him of abandoning an ally in the middle of a war, supporters of the president’s decision pointed to the Reagan precedent. If it was reasonable for the Republican presidential icon to limit arms to impose his will on Israel, they argue, it should be acceptable for the current Democratic president to do the same.

But what the Reagan comparison really underscores is how much the politics of Israel have changed in the United States since the 1980s. For decades, presidents and prime ministers have quarreled without permanently damaging the robust relationship between the two countries. Today, however, Israel has become a political lightning rod, perhaps more than ever.

In Mr. Reagan’s day, Democrats were thought to be the party that was more supportive of Israel, a perception he wanted to change. By Mr. Reagan’s own account, “they’ve never had a better friend of Israel in the White House.” And yet it was a friendship that was tested again and again.

In June 1981, less than five months after Mr. Reagan took office, Israel used U.S.-made F-16 warplanes to bomb the Osirak nuclear plant in Iraq, a surprise attack that outraged many in Washington. Defense Secretary Caspar W. Weinberger, considered a friend of the Arabs, urged Mr. Reagan to halt the arms flow to Israel. Secretary of State Alexander M. Haig Jr., considered a friend of Israel, argued against it.

In the end, Mr. Reagan agreed to vote to condemn Israel at the United Nations Security Council and to delay the delivery of four F-16s due that summer — what Patrick Tyler, in “A World of Trouble,” his history of U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East, characterized as “a minimal rebuke.”

But just weeks later, an Israeli airstrike killed an estimated 300 civilians in Palestinian neighborhoods of Beirut, prompting Mr. Reagan to hold back another 10 F-16s and two F-15 jet fighters. Still, the standoff did not last long. By August, Reagan lifted the freeze.

Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 forced another confrontation. Reagan halted the shipment of cluster-type artillery shells out of concern that such munitions were being used against civilians in violation of agreements. Around the same time, he delayed the delivery of 75 F-16 warplanes without explaining why until March 1983 when he announced that he would not release the jets until Israel withdrew forces from Lebanon.

The decision caused no firestorm of criticism like that seen in Washington this week. “Maybe it was a necessary signal to Israel,” Reagan wrote mildly in his diary that night in describing his decision. In the days that followed, stories in The New York Times included no criticism from members of Congress in either party. Not until a week later did William Safire, a conservative columnist for the Times, fault Reagan’s move as “a tragic flip-flop on Israel,” as he put it.

“Reagan had public support for withholding aid because the bombing of Beirut was witnessed on American television,” recalled Lou Cannon, the Reagan biographer. “As with Gaza, it was horrible.”

Since then, of course, Republicans have repositioned themselves as the party that unquestionably supports Israel while Democrats who bristle at Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s long conservative reign have become more divided on the issue. Today, there is none of the tempered deference that Reagan enjoyed from across the aisle on foreign policy.

The August 1982 bombardment in particular affected Reagan in a powerful way. Whatever his politics or policy, he reacted viscerally to the pictures he saw. “Reagan was deeply upset by the bombardment of Beirut,” Richard Murphy, his ambassador to Saudi Arabia, recalled in an oral history by Deborah Hart Strober and Gerald S. Strober. “He made it very plain that he wanted this to come to a stop when the human side was pushed in his face.”

Reagan did not hold back and was willing to put it all on the line. “I was angry,” he wrote in his diary that last night, describing the tense conversation with Begin. “I told him it had to stop or out entire future relationship was endangered.” And stop it did, at least temporarily.